Because you hear it on the BBC’s

Today programme or said by the Prime Minister’s spokesman doesn’t make it

acceptable English. John Humphrys, one of the presenters on the BBC’s Today programme has written at least two

books on the English language: Lost For Words: The Mangling and Manipulating

of the English Language’ insists that laBeyond Words’.

He is a much-respected journalist and broadcaster, he’s Welsh and therefore

knows a thing or two about language. All this does not stop him from using a bunch and stuff as well as give us a

sense of. I wish he wouldn’t. One of his colleagues, Sarah Montague, when

asked the other morning: how are you?

replied: Good. I really wish she

wouldn’t. John Humphrys is guilty of using sloppy Americanisms and Sarah

Montague of using sub-standard English. I should like them to be role models

for what used to be known as the Queen’s

English, to be people that

learners of English could use as a reference.

nguage should be simple,

clear and honest, and ‘

By drawing attention to the

following points, a few among many, I hope that learners of English will resist

the temptation to imitate the unfortunate habits of rather a lot of native

speakers who don’t care or who don’t know any other way of expressing

themselves. They follow verbal fashion and are often difficult to understand. I

know that sounds conceited, but that’s because I feel strongly about good English. An (*) indicates an

incorrect form, a solecism.

Fewer / less

*The less people who know, the

better. *He made less mistakes in the previous match.

This one is a marathon-runner; it

just keeps on going. In 2008, Tesco raised the hackles of many people by

putting up a sign at a till saying *10 items or less. They chose to replace it

by “Up to 10 items” rather than “10 items or fewer” on the grounds that it was

easier to understand. I suppose this might be called dumbing-down and may

explain why a lot of people have a problem with this distinction.

It's interesting to note that

"The less people know, the better" is grammatically a perfectly good

statement. So it's not simply a question of collocation.

Figures / numbers

It is now fashionable among some

financial journalists and analysts to talk about “the numbers” and nothing but

the numbers. There are stock market numbers, companies publish their numbers,

numbers are good or bad. Figures are disappearing. Why? This is American

influence again. Perhaps they think it sounds more professional or with it to

say numbers all the time. Numbers are mathematical symbols. When they have been

processed in some way, they magically become figures. Companies publish figures

or why not results? Numbers are things you dial on a telephone, or they

identify the house in the street where you live.

Station / train station

More transatlantic influence.

There is a concept known to linguists as “marked / unmarked terms”. It’s a most

useful idea, beautifully illustrated by this present pet hate of mine. In

British English, Station is unmarked,

it’s neutral, it's the place where you go to catch a train. Marked forms of station are bus station, power station, police station. If you want to use a

marked term to make sure there’s no misunderstanding about where to meet

somebody, why not call it a railway

station like we always have done.

Queue / Stand in line

This is moving in at a rapid

pace. Admittedly, queue is a funny

one to spell but is that an excuse for everybody to stand in line?

*For John and I

This is said by people who care

about the language, who have been taught at school that there’s something to be

careful about here but have forgotten what it is. What they were told is that John and I are great mates, but they don’t

like John and me. They explained this to John and me, but we didn’t understand.

After a preposition or as the object of a verb I becomes me. It happens

with the other pronouns, too: he/she/we/they

become him/her/us/them. It doesn’t

drive me mad, but when I hear it used correctly, I always mentally give the

speaker a couple of gold stars. A current TV advert for mis-sold insurance

claims, includes the following:..that

have been sold to you and I.

Out there

Out there is a very

frequently-heard thinking-stopper. It means everything and nothing. Its precise

meaning is what its two words indicate and no more. It’s best to leave it out.

Stuff

What can I say about “stuff”,

except “ouch”, another thinking-stopper. It seems to have completely taken over

from “things”, our own British home-grown thinking-stopper.

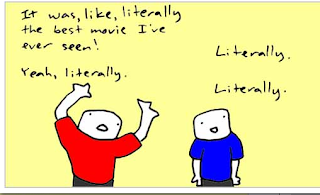

How are you? – *good

Another one moving in fast under

American influence. The cost of this type of fashion is that a pair of words,

in this case good/well, is reduced to one. The other one disappears in a

relatively short space of time and we have permanently lost a useful shade of

meaning.

Meet with

Nobody meets anybody anymore, but

they constantly meet with somebody. This has now got its feet under the table.

When I hear that somebody has met somebody, I pause for a few seconds and give

thanks.

Basis points

The British fashion-oriented

financial brigade ought to sort this one out. It's been around for a while, but

some of them still seem to think it's smart to use this American mumbo-jumbo.

Do 50 basis points better or more clearly express one half percent? Are 30

basis points 0.3% or not? Is it supposed to be simpler? It's nothing but

another useless layer of jargon

Sense

I am now finding the use of sense enervating: give us your sense of the situation, which has the value of understanding or feeling, is as annoying as give

us your take on the situation, another horror. If this continues much

longer the verbal use of sense: do you

sense that this situation is getting out of control? and the nominal use: common sense, the five senses, what sense are

you giving to this expression? are going to become confused. People will

begin to hesitate and possibly even avoid using the word.

If you listen to journalists,

there are specialists of the “one sense

fits all” school, like Norman Smith on the BBC. His excellent reports and

analyses contain lots of my sense of the

situation, which is a pity. This usage is taking over at the BBC.

To Grow a company

Growing companies now happens all the time. Tomatoes or potatoes, yes,

but companies, no.

Deliver

Everything is now delivered,

including education, policing and government. Provided? Nothing at all?

Impact

Earnings were impacted by the decline in oil prices, hit or

affected will do the trick. French needs this verb and has taken it. English doesn’t.

Used as a verb, there is a sense of physical contact, collision.

Bunch

A bunch of grapes, bananas, even a bunch of fives or hooligans, but

not a bunch of files, companies or books.

Key

When I was at school, we were not

allowed to use the adjective nice,

felt to be lazy, over-worked and almost meaningless, and we had to find another

word. I feel the same way now about the adjectival use of key. It has traditionally been used attributively as in key player, key industries, key factor.

It began to be used predicatively around 1970 and, like knotweed, is now all

over the place. Everything is key,

factors are key to our success, the use of military force is key in this

strategy. Hardly anybody says vital or

crucial any more. These two

adjectives are under threat.

To gift

27 per cent said they had gifted their items in the last month

(given away?)

To Pause

As a precaution the UK's A400M

aircraft are temporarily paused

(grounded?)

Referencing

Referencing Conservative pledges to cut the welfare budget

(regarding?)

Post

Post 1945. Post bellum, post hoc.

But, Post the EU referendum? Post lunch?

Multiple

It’s everywhere, multiple

sandwiches, multiple buses, multiple pairs of shoes. This used to be very restricted

in use: multiple injuries, fractures etc. Several

and many are going to disappear.

Firefighters

Firemen have disappeared.

First responders

Emergency services says it so much better.

Shooter

This is slightly ridiculous;

makes me think of pea-shooter or the dated

slang word for a pistol. Have

Americans forgotten the word gunman or

sniper?

It’s all about a lack of

elegance, style. Standards unfortunately only go in one direction, South, and

that’s another one that should be on my list.