For a long time, I’ve written

down my thoughts about and reactions to the way the English language is used or

misused today and it’s time I drew a conclusion or three. I’m not a collector

of things. The only collection I have is one of words and languages and usage.

To come across the following is a moment of discovery, of pleasure: “It's

thought that one in 50 people may have prosopagnosia,

or face blindness.” (BBC 010716). The OED defines it as: “An inability to

recognize a face as that of any particular person.” What a marvellous word;

fancy that, somebody gave it a name, a psychiatrist, of course.

I’ve spent a lot of time

expressing horror about things like: “Does the living wage mean less jobs?” (Press Association, 30 Sept

16) or gobbledygook such as: … your back

story, rather than your ideas, is of greatest importance.” (Spectator

15.10.16). I used to panic when I saw words like: salacity, to critique,

religiosity; they seem to be American creations but they go back a long way in

English history. Dangerosity, I always used to think it was an invention of

George W. Bush and indeed it must be; the OED doesn’t recognise it. George W.

is the President who wanted to do away with all taxes, including syntax. “Rallies

of this scale are unusual in Morocco.

(BBC).

A major complaint of mine has

been that we don’t have any discussion of language and grammar in our media,

written or spoken. The one exception I can think of is a weekly column in the

Spectator by Dot Wordsworth (sic), my apologies to her; it’s an interesting

column, if a little abstruse. Le Figaro published an interview with Julien

Barret on 01.11.16, entitled: «La langue

française est discriminante», discriminatory because Il y a une tyrannie du bon usage, there is a tyrannical concern with correctness. Mr Barret says there are

several types of French, some more correct than others. Of course, he’s right. He

cites the example of those who say, wrongly he claims, une pipe en écume de mer which is a corruption of the popular

French expression une pipe de Kummer. Whereas,

in fact, écume de mer is literally sea foam or meerschaum in German, which gives us our Meerschaum pipe.

Zoologists know this substance as sepiolite.

It doesn’t matter that this detail is incorrect; what counts is the discussion about

the French language. Le Figaro closes the article with an explanation of how to

avoid mistakes with one of the French language’s most troublesome points of

grammar, the agreement of the past participle. Most French speakers have

problems with this. I take my hat off to them. If only we could have similar

kinds of discussion in our newspapers.

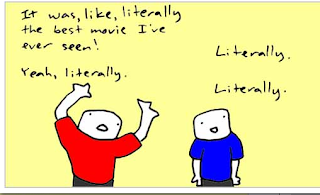

I have come to the conclusion that

the English language is now a fashion item. By talking about the numbers and going south you want to be identified with the financial community,

to be part of a clique. Others talk about the bottom line and begin every sentence with so because they think the American touch is best. But, there again,

it’s probably subconscious, like their taste in music, it’s simply just got to

be fashionable, or what they take to be fashionable. Ah, well.